August 2022

Matt Morse, who has worked in Legionella control and water treatment for over 20 years, both for service-providers and as an independent consultant, and works part-time as the Manager of the Legionella Control Association, discusses the subject of ‘competence’, with a particular focus on Legionella control. He focuses on what the term signifies, how it can be measured, and why it is so important into such a patient safety-critical field.

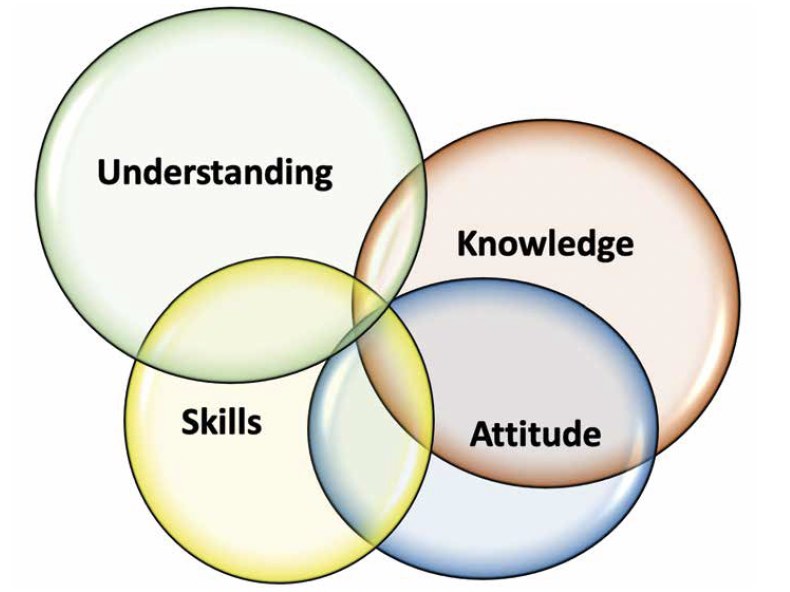

This article is about competence, specifically for Legionella control and management, but the principles could be applied to any area where a third party holds a duty to take reasonable steps to ensure that individuals are competent. Failings that lead to breaches in health and safety law, life-changing illness, and death, almost always have the thread of lack of competence running through them. Dutyholders can be prosecuted if these failings happen on their watch, regardless of the specialist advisor, Authorising Engineer (AE), or the contractor they have hired, and this sometimes comes as a surprise. So first, what is competence, and why is it important? Competence is often confused with training by duty-holders, AEs, Responsible Person(s) (RPs), et al, and while training is often a component of competence, they are certainly not the same thing. The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) states: ‘Competence can be described as the combination of training, skills, experience, and knowledge that a person has, and their ability to apply them to perform a task safely. Other factors, such as attitude and physical ability, can also affect someone’s competence.’ Training is the passing on of knowledge in some way, and includes classroom training, practical training, online training, on-the-job training, and pretty much any other ‘input’ of knowledge into an individual.

A fundamental building block

This underpinning knowledge is a fundamental building block of competence, but the individual needs to develop skills in the use of this knowledge to accomplish tasks safely, effectively, and efficiently. Building skill is normally achieved by watching others, performing tasks under supervision, being mentored, and with practice. This is unlikely to be possible purely in a classroom, so looking at training records may not give you the assurance you need.

What about certificates of competence?

There are some organisations that will issue a ‘certificate of competence’ after a training course. This may or may not be based on an assessment of the competence of an individual. To judge competence, this assessment would need to include an evaluation of the individual’s underpinning knowledge, understanding, and skills. The LCA has rejected applications for membership where the ‘certificate of competence’ was obtained following a one-day course in Legionella risk assessment. Clearly this cannot be sufficient to either absorb the knowledge required, or to assess the competence of the individual in question. These claims do not stand up to scrutiny, and should be challenged. On the other end of the spectrum there are competence-based Qualifications (with a capital ‘Q’) based on the National Occupational Standards,(1) and regulated by OFQUAL. These have learning and assessment hours in three figures, and are assessed by Qualified and Approved occupationally competent industry professionals. Sadly, due to the expense and the commitment required, these are not widespread, and many AEs and RPs have not heard of them. In the middle ground lies everything else, with a wide spectrum of quality. Some accreditation bodies will look at the training centre, but not the trainer or the course materials; others will look at the course material in detail and the delivery quality – ‘buyer beware’.

Competence lies where understanding, skills, attitude, and knowledge come together.

Employing contractors or consultants

ACoP L8(2) has a statement in paragraph 57 that says ‘employing contractors or consultants does not absolve the dutyholder of responsibility for ensuring that control procedures are carried out to the standard required to prevent the proliferation of legionella bacteria. Dutyholders should make reasonable enquiries to satisfy themselves of the competence of contractors in the area of work before they enter into contracts for the treatment, monitoring, and cleaning of the water system, and other aspects of water treatment and control. An illustration of the levels of service to expect from Service Providers can be found in the Code of Conduct administered by the Legionella Control Association (LCA)’. There are three important points in this paragraph:

- The legal duty remains with the dutyholder regardless of the employment of a specialist, so you remain responsible for the actions of your RP, AE, and contractors.

- Duty-holders should make ‘reasonable’ enquiries on competence, so possibly not that onerous, but certainly an interpretable term.

- Levels of service to expect can be found in the LCA Code of Conduct(3) – this seems like an easy way forward?

Matt Morse undertaking an ‘infield’ competence assessment.

Making ‘reasonable’ enquiries

Since you, as the duty-holder, are going to retain that responsibility, then the reasonable enquiries on competence are going to need to be made. Ask yourself, why do you believe that your AE, RP, consultant, risk assessor, clean and disinfection company, monitoring contractor, water treater, and so on, are competent. How do they prove it to you? There are registrations with professional bodies that might give you some comfort – or do they? That may depend on the entry criteria, and how these are assessed and policed.

Membership of trade associations generally involves a paid subscription, and gives little reassurance of the competence of the member companies, or the individuals registered by them. Professional bodies vary greatly. Some will require evidence of training, CPD, and references, to allow an individual to join, while others will have an element of peer-to-peer review; in some cases this may not have much value. Very little of this scrutiny focuses on the individuals that will be delivering services on your site – don’t forget, these are the people you need to be

making those ‘reasonable enquiries’ about.

Accreditation

What about accreditation and memberships that are often treated like accreditation, e.g. UKAS or the LCA? Does selecting a contractor that has this tick in the box get you off the hook for those ‘reasonable enquiries’? It may seem unlikely from reading L8? UKAS(4) is the UK body for accreditation to national standards. In the Legionella world it accredits laboratories to ISO standards for laboratory practices/ methods, and it accredits inspection bodies for Legionella risk assessment to the inspection standard, ISO 17020. Does this guarantee that every individual and every piece of work that a UKASaccredited company delivers is to the relevant standard? No – UKAS undertakes a sampling exercise of a company’s output, and cannot act as the QA department for the companies it accredits. The LCA is a standards organisation that grants membership to companies that operate appropriate management systems, and can demonstrate this with evidence at audit. The LCA requires members to comply with a Code of Conduct and Service Delivery Standards. The Service Delivery Standards(5) are about the technical delivery of Legionella control services, and are not the subject of this article, but the Code of Conduct has several clauses specific to competence of individuals that are very relevant. Does this guarantee that every individual and every piece of work that an LCA member company delivers is to the relevant standard? No – the LCA undertakes a sampling exercise of a company’s output, and cannot act as the QA department for member companies. This may seem like UKAS accreditation, except that the LCA has Service Delivery Standards covering all aspects of Legionella control services, not just risk assessment (ISO 17020) and analysis (ISO 17025), as UKAS does.

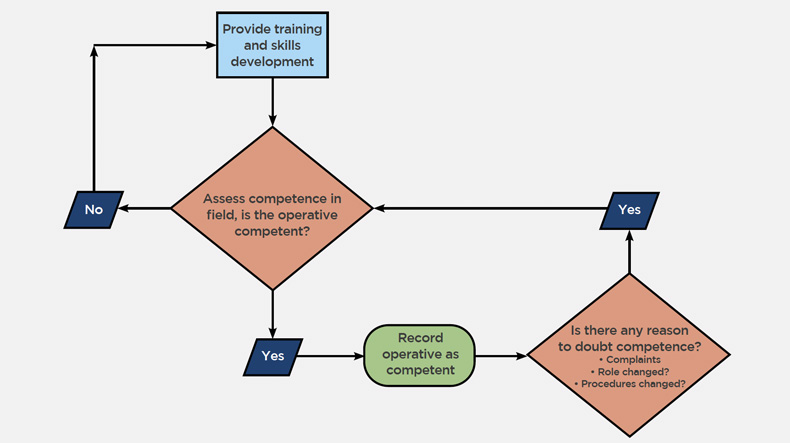

Key questions in the LCA competence assessment guidance.

Management system requirement

The LCA code section 2 (training and competence) requires member companies to operate a management system to identify what training is required to deliver the Legionella control work they do, and to make sure that their employees have that training, assess their competence to deliver that work, and to keep records of all of those. When the LCA audits a member company, we examine the structure around those elements to assess its capability. We then audit an LCA-selected sample of output that demonstrates that the system works, and is used in practice.

Identifying what you need to know to be able to do something sounds simple, but what if ‘you don’t know what you don’t know’? The LCA publishes a knowledge and skills matrix(6) to illustrate the knowledge and skills areas that members are likely to need for delivery of specific Legionella control tasks. Once the required knowledge is identified, looking at the staff to identify any gaps in their knowledge leads to the delivery of additional training to fill any gaps. Before working unsupervised, every member of staff must be assessed for their competence via an infield competence assessment. The LCA publishes guidance(7) on how to carry this out, and requires that records of these assessments and annual reviews are kept for all staff. What does all that mean for the user of the LCA member wanting to make those ‘reasonable enquires’?

An assurance of competence

Both UKAS accreditation and LCA membership mean that the company has to have in place management procedures that should lead to competent people being used on your site, job, or contract. Is the use of one of these accredited or member companies enough to discharge your legal duty to make those ‘reasonable enquiries’? By itself, not really. There is a bit more for the duty-holder to do: request the competence assessments for the staff that will be used on your work and review them. Take a look at examples of the individual’s previous work. Make a judgement based on that reasonable enquiry – you may not have the technical depth of knowledge to judge the individual; that is why you access this competent help in the first place. You can, however, request the backing detail for the company’s assertions that its staff are competent.

Competence in your contractors and staff is vital to avoiding breaches of the law, illness, and deaths. Use the tools available to make the necessary ‘reasonable enquiries’, and be wary of the huge variability in training quality that

exists in the marketplace.

References

1 COGWT11: Carrying out legionella risk assessments. National Occupational Standards. https://tinyurl.com/yc524j34

2 Legionnaires’ disease. The control of legionella bacteria in water systems. L8 Approved Code of Practice and guidance on regulations. Health & Safety Executive, 2013. https://tinyurl.com/yxdukpec

3 LCA Code of Conduct for LCA Members. Legionella Control Association. https://tinyurl.com/4v4pcduz

4 ‘Frequently Asked Questions’. UKAS. https://www.ukas.com/faqs/

5 LCA Standards. Legionella Control Association. https://tinyurl.com/y5u8devm

6 LCA Guidance. Suggested Knowledge & Skills Matrix for Legionella Control Service Delivery. Legionella Control Association. https://tinyurl.com/53zbrtne

7 Competence Guidance. Legionella Control Association. https://tinyurl.com/58yv68w6

Matt Morse

Matt Morse has worked in Legionella control and water treatment for over 20 years for service-providers and as an independent consultant, whose role includes including acting as a subject matter expert. He also works part-time as the Manager of the Legionella Control Association.

He has contributed to industry work including representation for industry bodies, and the development of guidance and standards. A pastchairman of the Legionella Control Association, he is a Member of the British Association of Chemical Specialities Water Treatment Group, a BSI committee member, and was a contributor to both the Health &

Safety Executive’s HSG274 guidance on Legionella, and the HSE Approved Code of Practice ACOP L8 (2013), Legionnaire’s disease: the control of Legionella in water systems.

He is a member of the Working Groups for the latest revision of BS 8580-1:2019: Risk Assessments for Legionella Control, for BS8680:2020: Water Safety Planning, and a current Working Group member for BS7592:2022: Legionella sampling, and BS 8580-2:2022: Risk assessments for Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other waterborne pathogens.

As first appeared in print in the August 2022 edition of Health Estate Journal (www.healthestatejournal.com), the monthly magazine of the Institute of Healthcare Engineering and Estate Management, ‘IHEEM’: www.iheem.org.uk.